The following is a transcript of an interview with Nathaniel Counts, J.D., Senior Policy Director from Mental Health America (MHA) that took place over the phone on February 3rd, 2017:

KDS: Why is it so important to find mental health problems early and to help children with them?

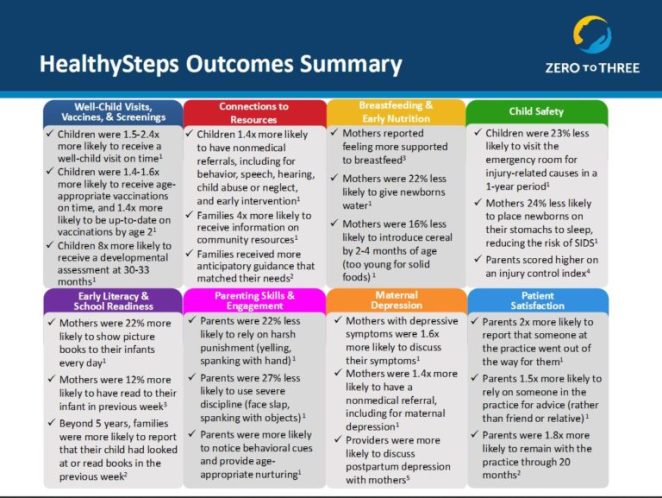

Nathaniel Counts, J.D.: I think a big part of it is there are things that we certainly don’t know enough of like self-treating and unintended consequences of symptoms. And then it’s easier to change their trajectory earlier in the process, the earlier you can intervene the better their whole course goes. It certainly interferes with school work and bad grades pile up, so that’s important to get in early and change.

What are some examples of policies that are currently in place and that are currently being considered to put in place to address these issues?

One of the big things is the preventive health essential health benefit and the Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule; those are the two mechanisms that mandate coverage for early intervention and prevention. They make it so you have to cover in the health insurance plan behavioral, social and development types of things in childhood and depression starting at age 11. One thing that actually is really exciting that came out was Medicare, and hopefully soon most Medicaid plans, will begin covering the collaborative care model which gives primary care providers a way to serve people with mental health issues in primary care so that you don’t have to see a psychologist or psychiatrist, that kind of specialty care. Which breaks down a major barrier to psychiatric care because I think most people would rather just get care from their primary care providers unless it’s a high level of acuity. That also saves specialty care resources because you don’t need someone at the doctor for every single issue.

You don’t even have to have a psychiatrist in the primary care setting. You could have the psychiatrist act as a consultant and the psychiatrist can function in a consultant capacity and provide case review or medication management. Then you could have someone like a nurse practitioner manage certain behavioral components. One of the things they could provide as a part of collaborative care is problem solving therapy or provide CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) style therapy in primary care.

Are there any current policies for early identification that you don’t agree with, that just aren’t working, or are inappropriate?

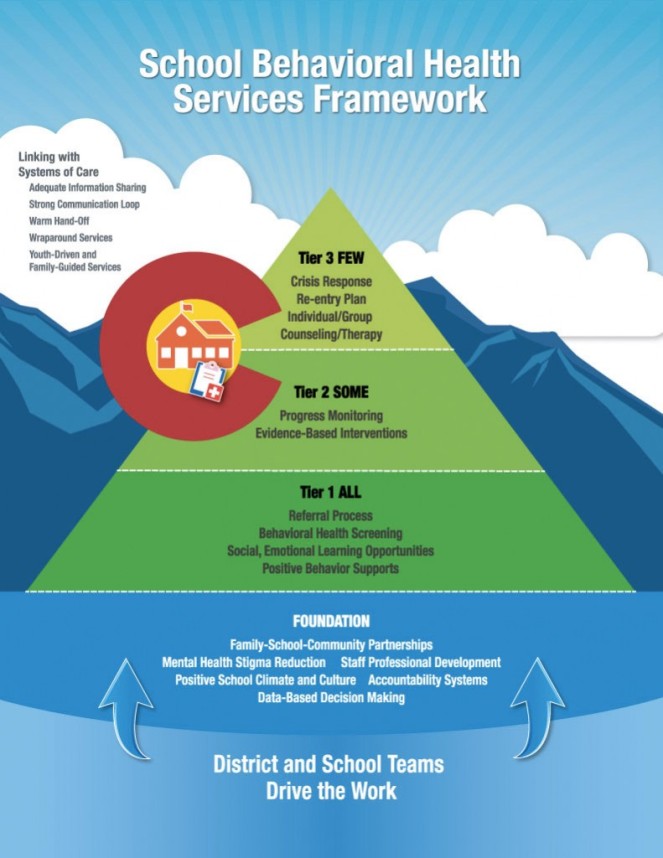

There’s not enough policy I’d say. One of the things that we’ve been battling with is the Individuals with Disabilities and Education Act (IDEA) which is a beautiful thing but it’s under-resourced and also individualization… you have to be quite sick for a lot of it to make sense or for it to function in the way that they’re after. What they’re after isn’t really behavioral, they’re only thinking about physical and medical disabilities, they aren’t really thinking about mental health. I think there’s ways you could implement IDEA that would help children behavioral health issues to get services and the support that they need.

What are you and the MHA currently doing to promote policies for early identification and treatment?

There’s two big things. The way that Value-Based Payment is currently structured it certainly systemically dis-incentivizes prevention. Under MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) you get quality incentive payments when you correctly manage someone’s depression but if you prevent their depression you get zero dollars. You lose out on the incentive payment entirely. It’s not the fault of MACRA because the problem is far more complex. There’s not actually good measures for providers to use to evaluate the quality of preventative interventions or the success of it for avoiding the problem entirely. Things like the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and they’re used in some capacities but they’re not used, and I’m not even sure that they’re appropriate, for value-based payment when they’re not condition specific psycho-social risk. So that’s one big area we’re working on is how do we crack pre-improvements that are pre-diagnosable disorders.

The second part of that is: how do you capture the benefits of that? One of the big problems with early intervention and prevention is health plans often have you on their plan for a year or two on average. So they don’t really get to see the benefits if they prevent something especially if you’re looking at something really important like nurse-family partnership that create really huge savings that accrue maybe twenty years later.

A big part of our work is to try to find ways that build in the logic of these cost savings into the model itself. There have decades of people arguing that we need to think longer term and across silos. That is another problem, a lot of the savings are in criminal justice and education and aren’t in healthcare at all. How do you build the logic of these saving models into the payment system? We work on community level policies that try to capture those realities and the healthcare payment models. Even something that were trying to figure out today is in accountable care organizations there’s supposed to protocols for care that are supposed to be reducing the amount of resources they’re using but there’s nothing built into to consider future resources that they’re not going to need to use. So the system dis-incentivizes these forward thinking interventions. A lot of it is trying to figure out how to rebuild the payment system so that it incentivizes this sort of work.

Then other people are taking on some of the related huge challenges like how do we train work forces that can actually use the interventions once they’re incentivized.

How do you make these changes happen on sort of a larger scale?

That’s sort of the complex thing. For building it into the payment system really we need to convince CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) that this is worth doing, which I think they would be convinced of if we could prove that these measures are ready for primetime. So part of it is a research issue. And then health plans need to have some sort of confidence that other health plans are going to be doing the same thing so they don’t have to foot the bill for all the prevention and get none of the benefits. So there’s the emerging All-Payer Model like Vermont, which I think is the most advanced, and Maryland has one to, which has all the payer share accountability for outcomes. That’s one example of a way to manage it.

Another way would be to have a preventative health essential benefit that you would mandate for everyone to try to achieve these incremental outcomes. But I think you would really need to have a system like that because otherwise they don’t really have any kind of incentive to do it. I don’t think anyone is really opposed to it either, I just think it’s the research isn’t there. All the people doing the prevention science research and all the people doing health system research are different people, so we spend a lot of time trying to unite these two fields.

On the payment issue, the problem is that actuarial science is how we decide to pay out for different things over time and how we understand how much of it is going to help different people. And there’s no concept of cross-sector actuarial science, how much someone will cost each different system. In a lot of cases these kinds of models that share benefits across sectors will need to be figured out politically on a community by community basis for the time being. Even some infrastructural backing at larger levels, I think people are going to have to hash out what they think is fair in their community to some extent.

Everyone is kind of sold on this stuff, but not enough people are mad about this. The thing is that if you give people a list of things to work on they’ll put this on their list but it’s hard to get it to the top of the list and the research isn’t really there either so the suggestion isn’t really that concrete.

We’re working with the scientists now that this opening is available, we’re trying to work with prevention scientists to use the common measures to begin to advance the case for using these in clinical practice but it needs to be a coordinated effort. The opportunity wasn’t there before until more recently so it will take time.

Looking at the early identification side, who do you think needs to be involved in the process of screening kids for mental illnesses? Is this something that should be left up to the schools or the pediatricians or is at an all hands approach where everyone needs to be involved?

I think we take a ubiquitous approach; we even have a partnership with Walgreens to get it into the pharmacy so you can just walk up to a little kiosk and take a screening. It can be something you can do at home, something you can do with a provider, something you can do with the school because one of the cooler part of cognitive behavioral therapy is the mood tracking. I think normalizing mental health by making it a part of everyone’s practice and start tracking progress, and mutually supporting one another would really add a lot.

You don’t want to tell people they’re disordered, that’s not the intention, if you do this so ubiquitously and see these things as scales and not as cut offs, per say, then you’re just sort of your tracking mental health. It’s not about identifying the broken people.

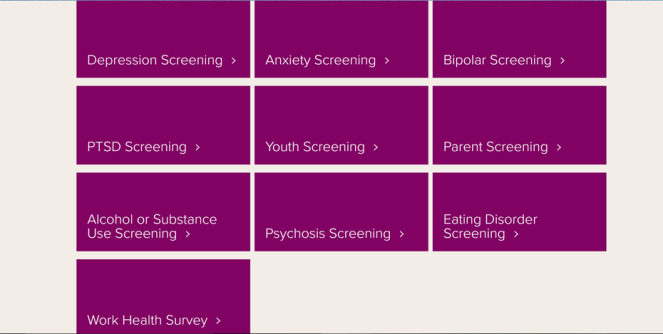

Are there any particular screening tools that the MHA recommends?

On MHAScreening.org, we have a whole set of clinically validated tools and people can use it any time to track their progress. There’s the PHQ-9 for depression, the pediatric symptoms checklist for children, the GAD-7 for anxiety.

There’s some pretty interesting interventions around well-being generally. There’s this initiative by Robert Johnson called 100 Million Healthier Lives where they’re coming up with community level well-being measures that the community can create on their own. It’s empowering for them to be able to take over their own well-being so there’s a macro structure on top of this, over this individual sense of mental health.

For the readers of my blog, is there anything in particular they can do promote this issue and get involved in it especially at the policy-making process level?

When you think about who is talking to policy-makers about these issues it tends to be people experiencing some kind of crisis, like parents of adult children who can’t access care or who can’t find a hospital bed and by then the problem is so advanced, so that tends to be all that is salient. I think even highlighting, one of the things we always harp on is preschool suspension and expulsion and the childcare suspension and expulsion are very prevalent and not at all a policy issue and that’s sort of the earliest signs and symptoms in a public way of these kinds of issues beginning to manifest. So making it salient for policy makers that we can be doing things and there is a crisis, it’s just nobody is calling at the moment. I think the sad thing is that parents internalize the child’s early social and emotional developmental issues, they think they’re tough children or struggling as a parent but it should be properly contextualized as a policy issue.

Is there anything else that you think would be important to talk about?

In the world of education there’s also social and emotional learning and that whole train of thought and mindset. I think it’s important to never think of them as different, they’re just all the same thing. They just got separated out by researchers and clinicians and I think it’s important to unit these trains of thought.

How can we do that? That’s kind of a tall order, right?

(Laughs) We’re working on it.

Part of it too is the way that we hope to use the same measures in education as we do in health so when we eventually decide on a set of measures, they get what the Institute of Medicine calls Core Developmental Competencies, like attachment and self-regulation and these kinds of things that we know make up the basis of healthy cognitive, affective, and behavioral development. Sort of unifying them across settings. So teachers share the same goal as pediatricians who share the same goal as parents, etc, etc.

So they’re using the same language and having the same perspective in mind. That makes sense.

And it’s also appreciating that it’s not about anyone being good or bad parents or pediatricians or whatever their role is. The science of child development is sort of un-intuitive in a lot of ways or hard to conceptualize. It’s not about getting back to parenting, I don’t think it’s about using empirical science. Every parent shouldn’t have to be their own scientist and recreate the whale, we should make it easy.

Thank you for taking the time out of your day to talk to me.

Good luck with your work and hopefully our paves will cross again soon.