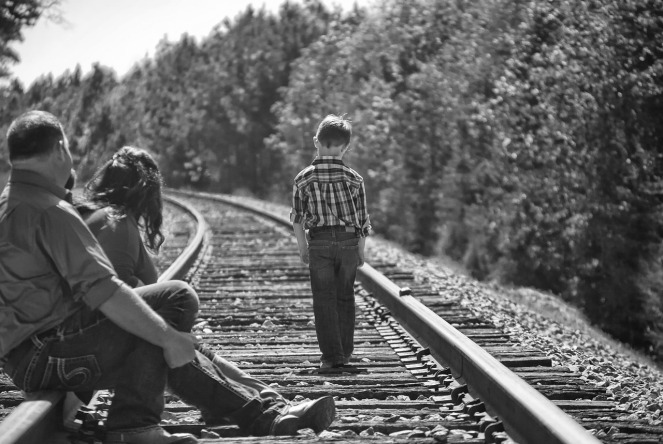

Chris’ mother, Jane, sits across from the school nurse in silence as the school nurse’s words sink in: “your son’s mental health screening showed symptoms of depression.” Jane thinks: that doesn’t make any sense, sure Chris has been a little moody lately and he hasn’t been hanging out with his friends as much or going to soccer practice but he’s becoming a teenager and isn’t that how teenagers just are? He’s just being a normal boy. Jane barely hears the school nurse over her own thoughts or the sinking sensation in her stomach “I recommend you take him to a doctor to be evaluated”. Jane’s stomach turns as she thinks: a doctor? An evaluation? Is it really that serious? It can’t be; my son is a normal kid, he’s not one of those kids who skulks around acting sullen and disgusted with the world. He’s not depressed. Not my child.

Hearing that your child might have a chronic illness is likely to be difficult whether it’s a condition that is labeled as physical or psychological but diagnoses of mental disorders tend to carry an extra weight created by stigma or misinformation. The images of people with mental illnesses created by media and works of fiction are usually inaccurate or exaggerated for entertainment value to the detriment of real people who live with these disorders. The resulting stigma creates ethical considerations that we as nurses should consider when developing policy for child mental health screening.

Longest describes ethical principles that should be weighed during the policy decision-making process; these include respect for autonomy and confidentiality, beneficence, and non-maleficence1.

Autonomy: Based on Jane’s reaction she might choose not to take her son to a psychiatrist for evaluation and treatment. Should the school nurse respect the mother’s decision or intervene to get treatment for Chris? As nurses, we recognize the need to respect the autonomy of our patients; this autonomy must also be taken into consideration when developing policy. In the case of child mental health screening, we need to consider making the screening optional as well as making subsequent evaluation and treatment optional if symptoms of mental health disorders are noted. When stigma is potentially interfering with the decision making process for the parent or child it is our duty to inform and to try to break down the stigma but not to override their wishes.

Confidentiality: Stigma against people with mental disorders enhances the need for confidentiality. As discussed earlier portrayal of people with mental disorders in entertainment media tends to be exaggerated and it is not uncommon for them to be depicted as violent offenders such as in the case of movie trailers for the recently released movie, Split, and its depiction of a person with Disassociate Identity Disorder https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84TouqfIsiI. In truth, a review by the Institute of Medicine found that people with mental illness contribute just a small to the overall rate of violence to the general population2. While confidentiality is important no matter what type of screening is being preformed, the stigma of mental illness increases the necessity of protecting the confidentiality of students whose screening suggests the presence of a mental disorder and should be taken into consideration during policy development and deciding who should be informed when screening results are positive.

Beneficence/Non-Maleficence: The principles of beneficence and non-maleficence must also be taken into consideration when developing health policy. Policy should be created with consideration of how it will benefit those who the policy will affect while minimizing negative effects. In this case, the intention of policy should be to benefit those children who are shown to have symptoms of a mental disorder through screening by providing referral for evaluation and treatment as soon as possible to mitigate the effects of illness. Conversely, some proponents of screening promote it out of concern for school violence perpetrated by children with mental illnesses. This perspective needs to be addressed with education for the public to dispel myths about violence in persons with mental illness and confidentiality should be maintained for children diagnosed with a mental illness in order to minimize harm. This is the intent of the principle of non-maleficence. We must also keep in mind the costs entailed to the school in carrying out these screenings and to the parents in getting their child treatment.

We, as nurses, should promote policy for screening children for mental disorders that will promote the greatest benefit for these children while minimizing costs to the child, parents, and to the school.

Jane sits at her kitchen table in her home studying the list of psychiatrists the school nurse had given to her earlier that day. The school nurse had described the symptoms of depression and the potential consequences of leaving the depression untreated as she had given Jane this list. Some of those symptoms do sound like things I’ve seen in Chris lately. What if he is depressed? The school nurse says he could start to feel hopeless and give up on school. He could give up on his future. He could give up on life. Jane looks over the list again. As she picks up her cellphone a feeling of determination and resolve swells inside of her: Not my child.

1Longest, B.B. (2010). Health policymaking in the United States (5th ed.). Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press.

2 Institute of Medicine (2006). Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine.

Autonomy is really important but where is the ethical line of abuse. I know there is something wrong with my child but I do nothing about it. Should policy intervene to define emotional abuse in that way?

LikeLike

This blog locates the ethical principles of respect for autonomy and confidentiality, beneficence, and non-malfeasance at the core of pediatric mental health screening policy. In line with the blog’s primary argument, these ethical principles should inform the policy decision-making process, particularly in situations involving children with mental health challenges. However, to effectively fight the stigma associated with mental health conditions in pediatric settings, I feel that it is important to broaden the scope of the principle of respect for autonomy to include a patient’s right to self-determination. Since children and their families have a moral and legal right to make a determination of what will be done with and to their own person, it is incumbent upon nursing professionals to undertake responsibilities that will ensure the realization of informed consent in dealing with mental health issues (Lanchman, 2016). Additionally, the “best interests” perspective could be used to address issues of stigma associated with mental health illnesses. When this utilitarian perspective is considered in such scenarios, parents will be more accommodative to the health discoveries made on their children and also to existing mental health policies since they will be looking at the interventions that offer the best possible solutions to the mental health challenges afflicting their children (Hendrix et al., 2016).

Reference:

Hendrix, K.S., Sturm, L.A., Zimet, G.D., & Meslin, E.M. (2016). Ethics and childhood vaccination policy in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 273-278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302952

Lachman, V.D. (2016). Ethics, law and policy: Ethical concerns in medical-surgical nursing. MEDSURG Nursing, 25, 429-432.

LikeLike

Hi Kelsey,

Again, great post! You are a talented blogger; I love your introductions and the way you pull us into your writing! You stated that the media and works of fiction can have a profound influence upon our perception of mental illness, and I strongly agree with you. I often work with clients who are fearful and embarrassed that they are receiving behavioral health services – “I’m not crazy, I swear,” they tell me. “I’ve never had to see a shrink before in my life.” “Am I messed up like that person in the movie ‘Split?'” “Are you going to operate on me like that guy in ‘One Few Over the Cuckoo’s Nest?'” The stigma/fear of mental illness is so great that these individuals often avoid seeking care until their depression, anxiety, etc has become debilitating. Thus, it is understandable that children and their guardians are reluctant to attribute thoughts and feelings to a mental illness. In addition to screening for mental illness, perhaps we should also work on generating a policy which encourages increased mental health education in pediatric offices. Such a policy would promote beneficence by alleviating parents’ fears and encouraging adherence toward behavioral health care. Additionally, pediatricians who are trained to screen and treat mental illness may have greater success in encouraging mental health care in children. A recent study found that children prefer – and are more compliant – with mental health services received from their pediatrician rather than a mental health care professional (Smydo, 2014). Thus, increased screening, mental health education, and mental health care in the pediatric office may assist in promoting beneficence and higher quality of patient care.

Reference

Smydo, J. (2014). Children prefer mental health care at office of pediatrician. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved from http://www.post-gazette.com/news/health/2014/03/24/Children-prefer-mental-health-care-at-office-of-pediatrician/stories/201403240052

LikeLike

This post beautifully illustrates the need for mental health screening at occur at an early age. Despite the prevalence of psychiatric disorders, many individuals go without treatment due to being undiagnosed or being misdiagnosed (Ali, Teich, & Mutter, 2015). Under-recognition of psychiatric disorders is common and results in substantial delay in diagnosis, subsequent initiation of treatment, and poorer outcomes (Patel et al., 2015). Additionally, statistics illustrate that approximately 50% of chronic mental health conditions start by age 14 and the average delay for intervention is 8-10 years (NAMI, 2017). If early recognition and treatment equals better lifetime success and quality of life, it seems to reason that a policy to support childhood screening (and treatment if indicated) is a clear choice.

In addition to a policy to support screening, I believe that healthcare professionals have an ethical responsibility to assist in the effort to reduce stigma associated with mental health disorders. Livingston and Boyd (2010) share that the social effects of stigma include exclusion, poorer quality of life, limited social support, and low self-esteem. Reduction in stigma must be paired with improved identification and treatment, so as to allow better outcomes for the population at large.

References

Ali, M.M., Teich, J.L., & Mutter, R. (2015). The role of perceived need and health insurance in substance use treatment: Implications for the affordable care act. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 54, 14-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.02.002

Livingston, J. D. & Boyd, J. E. (2010). Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 71 (12), 2150-2161.

NAMI. (2017). Mental health screening. Retrieved from: https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Public-Policy/Mental-Health-Screening

Patel, R., Shetty, H., Jackson, R., Broadbent, M., Stewart, R., Boydell, J., Mcguire, P., & Taylor, M. (2015). Delays before diagnosis and initiation of treatment in patients presenting to mental health services with bipolar disorder. PLoS One, 10(5), e0126530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126530.

LikeLike